An Introduction to Stochastic Calculus and Itô's Lemma

I’ve been working on diffusion models since mid 2022 and one thing that raised my particular interest is understanding the hidden machinery about these models. One approach to understand (continuous-time) diffusion models, is through the lens of stochastic differential equations (SDEs)1. As the name reveals, some common understanding of stochastic calculus is necessary. If you’re like me and learned regular calculus first in school and university, SDEs can feel a bit mysterious and scary at first. So here’s my attempt at explaining what I’ve learned before diving into the deeper mathematics of diffusion SDEs.

When working with SDEs, we’re dealing with stochastic processes $X_t$—think of them as random paths that evolve over time. Each time you run the process, you get a different trajectory. In principle, these processes can run forever ($T=\infty$), making them infinite-dimensional objects. For now, we’ll keep things simple with $X_t \in \mathbb{R}$. Real-world examples might include Stock prices, population dynamics, or even the pH level of a chemical solution.

Outline: We’ll start with why $(dW_t)^2 = dt$ (quadratic variation), then build up stochastic integrals and Itô’s Lemma. Along the way, we’ll solve some classic SDEs and end with Brownian motion on a circle—showing how geometry and randomness interact.

A note on expectations: I mean the mathematical kind, though let’s see if this post lives up to your other expectations too. When we write $\mathbb{E}[X_t]$ or $\mathbb{E}[f(X_t)]$, what are we averaging over? We’re averaging over all possible sample paths the stochastic process could take. Imagine running the process many times. Each run gives you a different random path. The expectation is the average value across all these paths. In practice, you can think of simulating 10,000 Brownian motion paths: the expectation is what you’d get by averaging the quantity of interest across all 10,000 runs (see later simulations).

Quadratic Variation

In regular calculus, when you have an infinitesimal $dx$, the square $(dx)^2$ is so small we ignore it. But Brownian motion $W_t$ is “rough” enough that the following holds

\[(dW_t)^2 = dt \tag{1}.\]Where does this come from? Let’s first define quadratic variation properly, then derive this result.

Definition: The quadratic variation of a stochastic process $X_t$ over $[0, T]$ is

\[\lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (X_{t_i} - X_{t_{i-1}})^2,\]where $0 = t_0 < t_1 < \cdots < t_n = T$ is a partition of $[0, T]$ with grids going to zero as $n \to \infty$. For Brownian motion, this limit exists and equals $T$.

To derive this, consider partitioning the interval $[0, T]$ into $n$ equal subintervals with $\Delta t = T/n$. The sum of squared increments is

\[\sum_{i=1}^{n} (W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})^2.\]Each increment $(W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})$ is Gaussian, that is, $(W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}}) \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \Delta t)$, and increments are independent, meaning the value of $(W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})$ doesn’t tell you anything about $(W_{t_j} - W_{t_{j-1}})$ for $i \neq j$. This is what makes the process memoryless—increments at different times don’t know about each other.

Expected value: For a Gaussian random variable with variance $\Delta t$, the expected squared value equals its variance such that

\[\mathbb{E}[(W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})^2] = \Delta t.\]This holds because the increment has zero mean: $\mathbb{E}[W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}}] = 0$, so $\text{Var}[W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}}] = \mathbb{E}[(W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})^2] - (\mathbb{E}[W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}}])^2 = \mathbb{E}[(W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})^2]$.

So the expected value of the entire sum is

\[\mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{i=1}^{n} (W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})^2\right] = \sum_{i=1}^{n}\mathbb{E}\left[ (W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})^2\right] = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \Delta t = n \cdot \Delta t = T.\]This means the quadratic variation fluctuates around $T$ such that

\[\mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{i=1}^{n} (W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})^2 \right ] - T = 0.\]Variance of the sum: For a squared Gaussian $Z^2$ where $Z \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)$, we have $\text{Var}[Z^2] = 2\sigma^4$.

Why? Using the rule $\text{Var}[X^2] = \mathbb{E}[X^4] - (\mathbb{E}[X^2])^2$. For a centered Gaussian, $\mathbb{E}[Z^2] = \sigma^2$ and $\mathbb{E}[Z^4] = 3\sigma^4$ (the fourth moment), so $\text{Var}[Z^2] = 3\sigma^4 - (\sigma^2)^2 = 2\sigma^4$.

Therefore

\[\text{Var}[(W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})^2] = 2(\Delta t)^2.\]Since the increments are independent, the variance of the sum is

\[\text{Var}\left[\sum_{i=1}^{n} (W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})^2\right] = n \cdot 2(\Delta t)^2 = 2T^2/n \to 0 \text{ as } n \to \infty.\]As we make the partition finer, something cool happens: the randomness washes out and the sum approaches $T$. The sum of squared increments becomes more predictable, not more random. This is the quadratic variation of Brownian motion—it’s non-zero and becomes deterministic in the limit.

Differential notation: Since the quadratic variation over $[0, T]$ equals $T$, the quadratic variation over any infinitesimal interval $[t, t+dt]$ equals $dt$. In differential form, this gives us equation (1)

\[(dW_t)^2 = dt.\]This is what makes stochastic calculus different from regular calculus. When we later do Taylor expansions and decide which second-order terms to keep, we can’t ignore $(dW_t)^2$ because it equals $dt$, not zero.

Integral form: We can also express the quadratic variation as an integral. Taking the limit of the discrete sum

\[\lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})^2 = \int_0^T (dW_t)^2 = \int_0^T dt = T.\]In other words, the “integral” of $(dW_t)^2$ over time is just ordinary integration of $dt$.

If you want to dig deeper, Øksendal’s book2 (Chapter 3) and Gardiner3 (Chapter 4.2) have the full details.

Random Fluctuations through Brownian Motion

Brownian motion $W_t$ is our fundamental noise source. Think of it as a continuous random walk. It starts at zero ($W_0 = 0$), and each increment $W_t - W_s$ is Gaussian with variance $t - s$. Importantly, increments at different times are independent: the past doesn’t influence the future.

The simplest SDE is just pure Brownian motion: $dX_t = dW_t$. Imagine a particle whose position $X_t$ changes randomly at each instant—no drift, just noise. Let’s see what this looks like:

Show simulation code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

np.random.seed(42)

T, n_steps, n_paths = 1.0, 500, 5

dt = T / n_steps

t = np.linspace(0, T, n_steps + 1)

# Brownian motion: cumulative sum of Gaussian increments

dW = np.sqrt(dt) * np.random.randn(n_paths, n_steps)

W = np.zeros((n_paths, n_steps + 1))

W[:, 1:] = np.cumsum(dW, axis=1)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4))

for i in range(n_paths):

plt.plot(t, W[i], alpha=0.8)

plt.xlabel('t'); plt.ylabel('$X_t$')

plt.title('Sample Brownian Motion Paths')

plt.show()

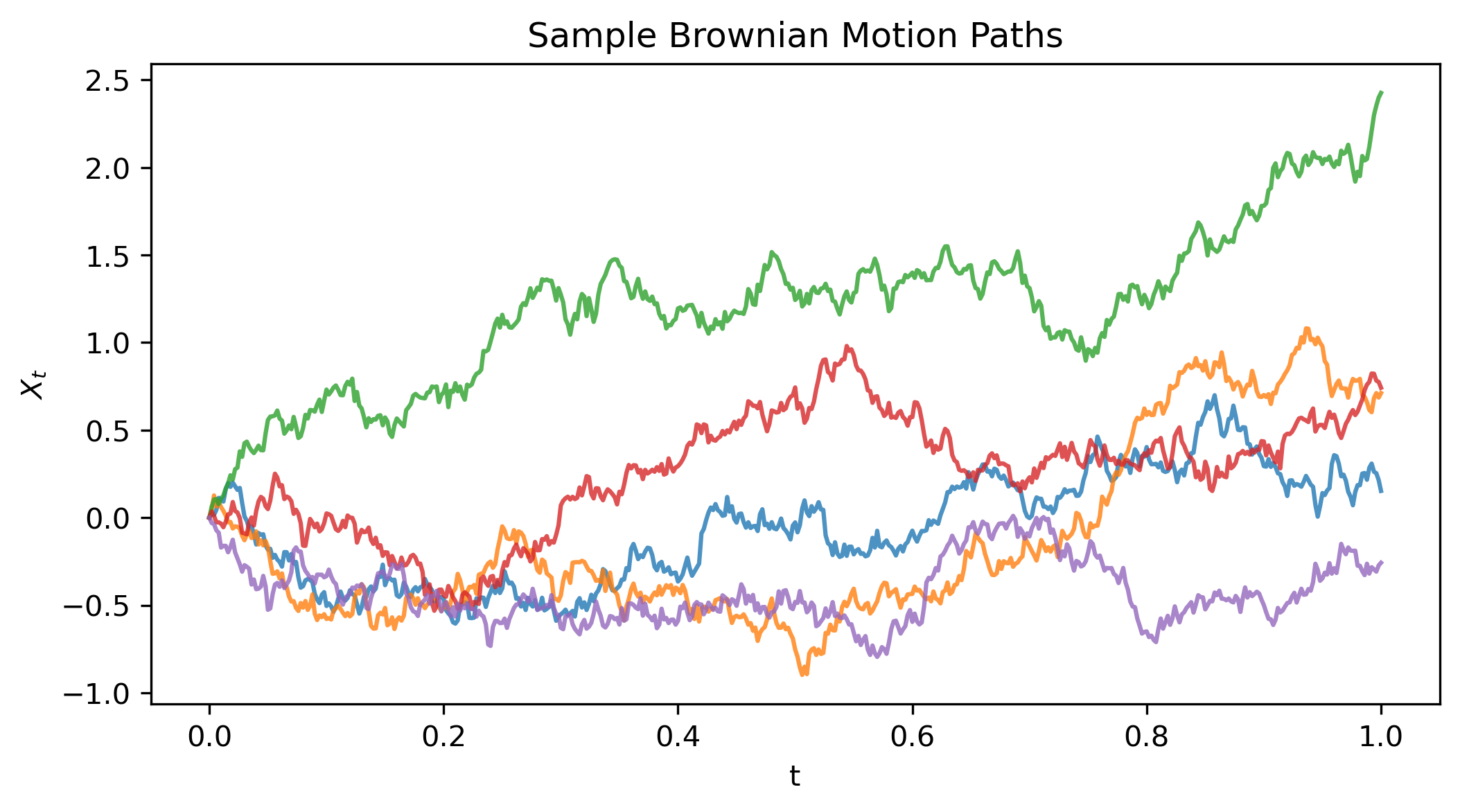

Figure 1: Sample Brownian motion paths starting from zero, each taking a different random trajectory.

Figure 1: Sample Brownian motion paths starting from zero, each taking a different random trajectory.

Each path starts at zero and moves randomly: some drift up, others down. The important point: increments dW = np.sqrt(dt) * randn() have variance dt, which is why $(dW)^2 \sim dt$.

Stochastic Integrals

Before we can solve SDEs, we need to understand stochastic integrals. Unlike ordinary integrals where you integrate with respect to $dt$, here we integrate with respect to Brownian motion $dW_t$. Think of it as multiplying a function by random noise and summing up the results over time. Remember those random paths from Figure 1? Stochastic integrals are built from exactly those Brownian increments.

The simplest case: What is $\int_0^t dW_s$?

Since $W_t$ is the integral of its own differential, we have

\[\int_0^t dW_s = W_t - W_0 = W_t.\]since $W_0 = 0$. Think of it as the position of a particle undergoing Brownian motion (like the paths shown in Figure 1) at any time $t$.

This is just the fundamental theorem of calculus: integrating the differential gives you back the function. Same as $\int_0^t ds = t$, but now with randomness.

More generally: For a deterministic function $g(t)$, the Itô integral is

\[\int_0^t g(s) \, dW_s.\]This is defined as the limit of Riemann-like sums: partition $[0, t]$ into small intervals and approximate

\[\sum_{i=1}^n g(t_{i-1}) (W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}}).\]Notice we evaluate $g$ at the left endpoint $t_{i-1}$ as this is the Itô convention. As the partition gets finer, this sum converges to the stochastic integral.

Two key properties: First, the integral $\int_0^t g(s) \, dW_s$ is a random variable (depends on which Brownian path you get). Second, it has mean zero: $\mathbb{E}\left[\int_0^t g(s) \, dW_s\right] = 0$. Remember the expectation averages over many Brownian paths as mentioned earlier.

Why mean zero? Remember the integral is built from the sum $\sum_i g(t_{i-1})(W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})$. Each Brownian increment has zero mean: $\mathbb{E}[W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}}] = 0$. Since $g(t_{i-1})$ is deterministic (known at the previous time step), we have $\mathbb{E}[g(t_{i-1})(W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})] = g(t_{i-1}) \mathbb{E}[W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}}] = g(t_{i-1}) \cdot 0 = 0$. The expected value of the sum is zero, so the integral has mean zero.

- Its variance is given by the Itô isometry

What does Itô isometry mean? It tells you how variance accumulates over time. When $g(s)$ is large at some moment $s$, the noise gets amplified there, contributing more to the total variance. The formula is elegant: variance of the stochastic integral = ordinary time integral of $g(s)^2$.

This formula appears in many applications, like computing variances of stochastic processes, proving that numerical methods like Euler-Maruyama converge, or finding stationary distributions (as we’ll do later for the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process).

Example: For $\int_0^t s \, dW_s$, equation (2) gives variance $= \int_0^t s^2 \, ds = \frac{t^3}{3}$.

Numerical simulation: Let’s check the Itô isometry with two cases: $g(s) = 1$ and $g(s) = s$. We’ll simulate 10,000 Brownian paths until time $T=1$, compute the stochastic integral for each path (each one is a random variable), and then verify that the mean and variance across all paths match the theoretical results from Itô isometry.

Show simulation code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

np.random.seed(42)

T = 1.0

n_steps = 500

n_paths = 10000

dt = T / n_steps

t_grid = np.linspace(0, T, n_steps)

# Generate Brownian motion paths

dW = np.sqrt(dt) * np.random.randn(n_paths, n_steps)

W = np.cumsum(dW, axis=1)

# Case 1: g(s) = 1

# The stochastic integral is simply W_T

integral_constant = W[:, -1]

var_constant = T

# Case 2: g(s) = s

# Using left-endpoint approximation: sum of g(t_{i-1}) * dW_i

integral_linear = np.zeros(n_paths)

for i in range(n_steps):

g_value = t_grid[i] # g(s) = s evaluated at left endpoint

integral_linear += g_value * dW[:, i]

var_linear = T**3 / 3

# Create side-by-side plots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 5))

# Plot 1: g(s) = 1

axes[0].hist(integral_constant, bins=50, density=True, alpha=0.7,

label=f'Simulated (mean={np.mean(integral_constant):.3f}, var={np.var(integral_constant):.3f})')

x1 = np.linspace(-4, 4, 100)

axes[0].plot(x1, 1/np.sqrt(2*np.pi*var_constant) * np.exp(-x1**2/(2*var_constant)),

'r-', linewidth=2, label=f'Theory: $\mathcal(0, {var_constant:.3f})$')

axes[0].set_xlabel(r'$\int_0^T dW_s = W_T$')

axes[0].set_ylabel('Probability Density')

axes[0].set_title('$g(s) = 1$ (constant)')

axes[0].legend()

axes[0].grid(alpha=0.3)

# Plot 2: g(s) = s

axes[1].hist(integral_linear, bins=50, density=True, alpha=0.7,

label=f'Simulated (mean={np.mean(integral_linear):.3f}, var={np.var(integral_linear):.3f})')

std_linear = np.sqrt(var_linear)

x2 = np.linspace(-3*std_linear, 3*std_linear, 100)

axes[1].plot(x2, 1/np.sqrt(2*np.pi*var_linear) * np.exp(-x2**2/(2*var_linear)),

'r-', linewidth=2, label=f'Theory: $\mathcal(0, {var_linear:.3f})$')

axes[1].set_xlabel(r'$\int_0^T s \, dW_s$')

axes[1].set_ylabel('Probability Density')

axes[1].set_title('$g(s) = s$ (linear)')

axes[1].legend()

axes[1].grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.suptitle('Stochastic Integral Distributions for Different Functions $g(s)$',

fontsize=14, y=1.02)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

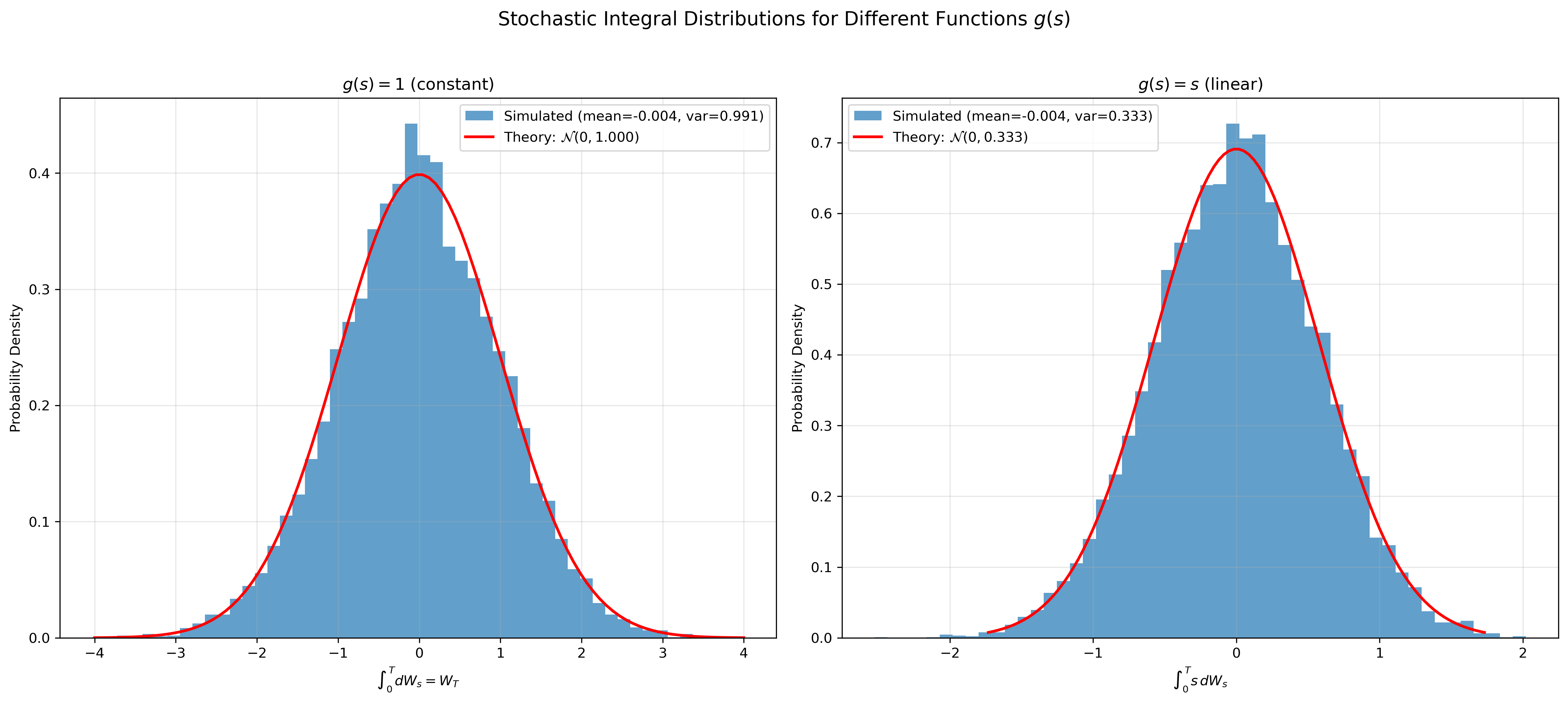

Figure 2: Distribution of stochastic integrals for two different functions: $g(s)=1$ (left) and $g(s)=s$ (right). Both are Gaussian with different variances.

Figure 2: Distribution of stochastic integrals for two different functions: $g(s)=1$ (left) and $g(s)=s$ (right). Both are Gaussian with different variances.

The simulation confirms the Itô isometry: we computed 10,000 stochastic integrals (one for each sample path). Each individual integral $\int_0^T g(s) \, dW_s$ is a random variable. The histograms show the distribution of these random variables across all paths. For $g(s) = 1$, the empirical variance matches the theoretical prediction $T = 1$ and for $g(s) = s$, variance = $T^3/3 \approx 0.333$. Notice how the linear function produces a narrower distribution since its variance is smaller.

Wait, the distributions look Gaussian, right? The stochastic integral $\int_0^T g(s) \, dW_s$ is built from a sum of Gaussian increments: $\sum_i g(t_{i-1}) (W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})$. Each increment $(W_{t_i} - W_{t_{i-1}})$ is Gaussian, and since the sum of independent Gaussian random variables is itself Gaussian, the integral inherits this property in the limit. This connects to the Central Limit Theorem (CLT): even if the increments weren’t exactly Gaussian, the CLT tells us that sums of many independent random variables tend towards a Gaussian distribution. But here we have an even stronger result, since the increments are already Gaussian, the sum stays Gaussian at every stage. More formally, the stochastic integral is Gaussian with mean zero and variance given by the Itô isometry (equation 2). This is why we can predict the entire distribution from the integrand $g(s)$.

Stochastic Differential Equations

An SDE captures both deterministic and random dynamics in one equation:

\[dX_t = \mu(X_t, t) \, dt + \sigma(X_t, t) \, dW_t. \tag{3}\]The first term $\mu(X_t, t): \mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ pulls the system in a predictable direction (the drift), while the second term adds randomness through the diffusion coefficient $\sigma(X_t, t) : \mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^+$.

Notice that the SDE in equation 3 is in differential form. We can also re-write the equation into integral form (see Chapter 5.2 in Øksendal’s Stochastic Differential Equations2), since we discussed stochastic integrals in the previous section.

\[X_t = X_0 + \int_{0}^t \mu(X_s, s)ds + \int_{0}^t \sigma(X_s, s) \, dW_s.\]When we can’t solve an SDE analytically, we approximate this integral numerically—exactly what we did for the Brownian motion paths earlier.

A classic example is the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process defined by

\[dX_t = -\theta X_t \, dt + \sigma \, dW_t, \tag{4}\]with $\theta, \sigma > 0$. The $-\theta X_t$ term keeps pulling the process back toward zero, while noise perturbs it. Note that the diffusion coefficient is state independent and only scales the random fluctuation $dW_t$. This is basically what happens in diffusion models during the forward process as explained in Appendix B in 1.

Here’s a simulation using the Euler-Maruyama method over a longer time period to see the mean-reverting behavior:

Show simulation code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

np.random.seed(42)

T, n_steps, n_paths = 5.0, 1000, 5

dt = T / n_steps

t = np.linspace(0, T, n_steps + 1)

# OU parameters

theta = 2.0 # mean reversion speed

sigma = 0.5 # volatility

# Simulate OU process: dX = -theta * X * dt + sigma * dW

X = np.zeros((n_paths, n_steps + 1))

X[:, 0] = np.random.randn(n_paths) # start at random positions

for i in range(n_steps):

dW = np.sqrt(dt) * np.random.randn(n_paths)

X[:, i+1] = X[:, i] - theta * X[:, i] * dt + sigma * dW

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4))

for i in range(n_paths):

plt.plot(t, X[i], alpha=0.8)

plt.axhline(0, color='k', linestyle='--', alpha=0.3, label='Mean (0)')

plt.xlabel('t'); plt.ylabel('$X_t$')

plt.title('Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Process: Mean Reversion in Action')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

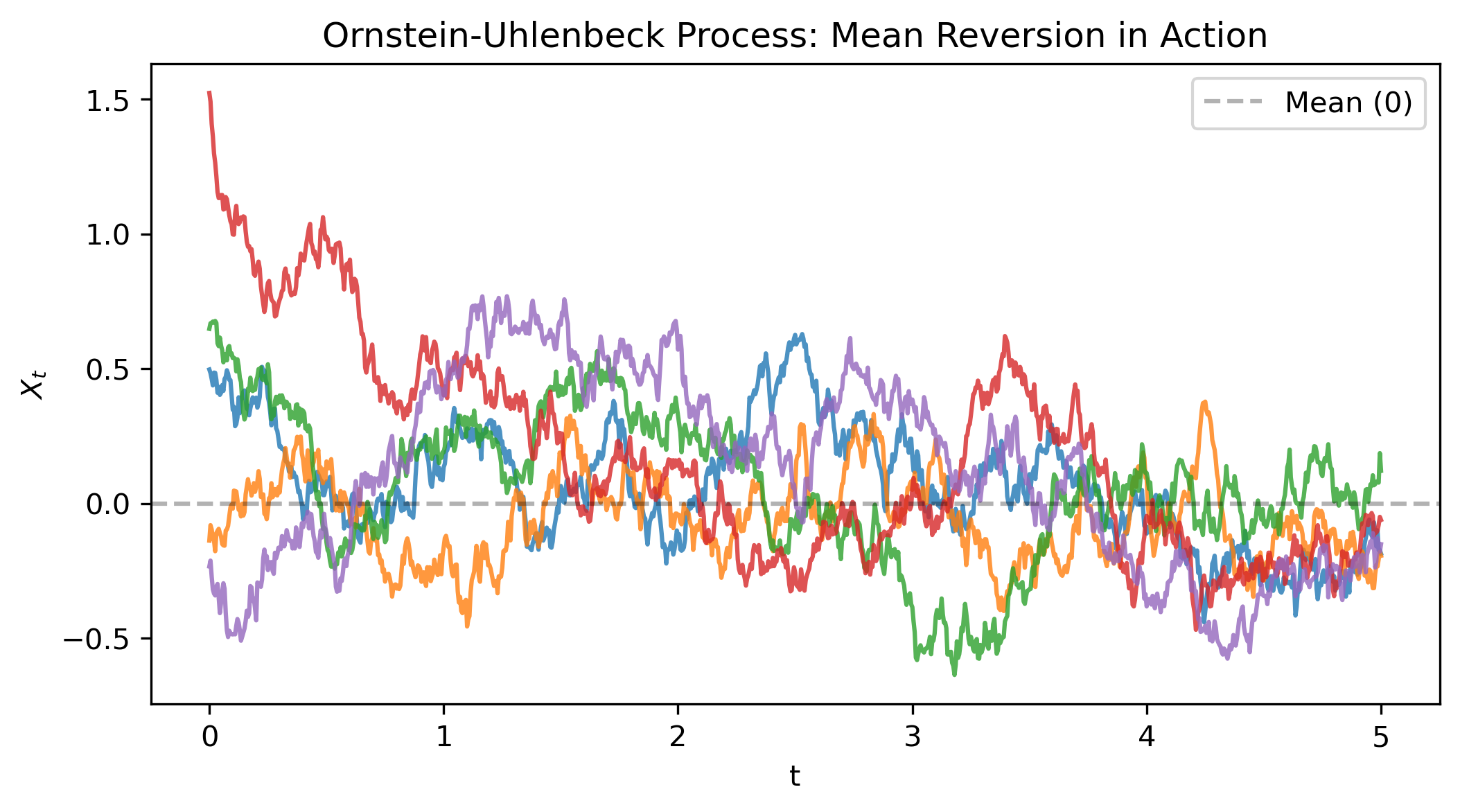

Figure 3: Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process showing mean reversion—paths are continuously pulled back toward zero.

Figure 3: Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process showing mean reversion—paths are continuously pulled back toward zero.

Notice how the paths keep getting reverted back to zero. Unlike Brownian motion (Figure 1), which wanders off indefinitely, the OU process has a stationary distribution. We’ll derive the explicit solution once we cover Itô’s Lemma.

Itô’s Lemma

Here’s the big question: if we have some function $f(X_t)$, how does it evolve when $X_t$ is stochastic? In regular calculus, we’d just use the chain rule: $df = f’(X) dX$.

But in stochastic calculus, there’s a twist—we get an extra term. For a process $X_t$ satisfying

\[dX_t = \mu(X_t, t) \, dt + \sigma(X_t, t) \, dW_t\]and a smooth function $f(x, t)$, we start with a Taylor expansion

\[df = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} dX_t + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial t^2} (dt)^2 + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} (dX_t)^2 + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial t \partial x} dt \, dX_t + \ldots\]We truncate the Taylor series by keeping only terms of order $dt$. In ordinary calculus, all second-order terms like $(dt)^2$ are negligible. But here’s where stochastic calculus differs: some second-order terms are actually of order $dt$ and can’t be ignored. Let’s see which ones survive.

First, $(dX_t)^2$: Substituting $dX_t = \mu \, dt + \sigma \, dW_t$ gives

\[(dX_t)^2 = (\mu \, dt + \sigma \, dW_t)^2 = \mu^2 (dt)^2 + 2\mu\sigma \, dt \, dW_t + \sigma^2 (dW_t)^2.\]Now we apply the rules (in Särkkä’s Applied Stochastic Differential Equations4 Theorem 4.6):

- $(dt)^2 = 0$ — higher-order infinitesimal, vanishes

- $dt \cdot dW_t = 0$ — higher-order infinitesimal, vanishes

- $(dW_t)^2 = dt$ — from equation (1), this is the key difference and was derived in the Quadratic Variation section

So $(dX_t)^2 = \sigma^2 \, dt$, which is not negligible.

The other second-order terms are

- $(dt)^2 = 0$

- $dt \cdot dX_t = dt \cdot (\mu \, dt + \sigma \, dW_t) = \mu(dt)^2 + \sigma \, dt \, dW_t = 0$

Only the $(dX_t)^2$ term remains. This gives us Itô’s Lemma

\[df = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} dX_t + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} \sigma^2 \, dt. \tag{5}\]The last term—the Itô correction—is purely from the roughness/ quadratic variation of Brownian motion.

Expanding everything out by substituting the differential results into

\[df = \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} + \mu \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} + \frac{\sigma^2}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} \right) dt + \sigma \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} dW_t. \tag{6}\]So Itô’s Lemma is basically Taylor expansion for stochastic processes, keeping everything of order $dt$, including the important second-order term from $(dW_t)^2 = dt$.

Geometric Brownian Motion

Now that we have learned about Itô’s Lemma, let’s solve the geometric Brownian motion

\[dX_t = \mu X_t \, dt + \sigma X_t \, dW_t,\tag{7}\]where $\mu\in \mathbb{R}, ~ \sigma>0$. Here both the drift and diffusion depend on the state (unlike before). This falls into the family of linear multiplicative noise processes because the SDE is linear in $X_t$, but the “noise term” $dW_t$ multiplies $X_t$. (See Gardiner’s Handbook of Stochastic Methods3 Chapter 4.4.2 or Särkkä’s Applied Stochastic Differential Equations4 Example 4.6)

The trick is to look at $Y_t = \log X_t$ to solve the SDE. We’ll apply Itô’s Lemma (equation 5) with $f(X, t) = \log X$ and solve it through the following steps.

Step 1: Compute the partial derivatives. For $f(X, t) = \log X$:

- $\frac{\partial f}{\partial t} = 0$ (no explicit time dependence)

- $\frac{\partial f}{\partial X} = \frac{1}{X}$

- $\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial X^2} = -\frac{1}{X^2}$

Step 2: Apply Itô’s Lemma. Using equation (5) with $\mu(X_t, t) = \mu X_t$ and $\sigma(X_t, t) = \sigma X_t$:

\[dY_t = d(\log X_t) = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial f}{\partial X} dX_t + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial X^2} \sigma(X_t, t)^2 \, dt\]Substituting the derivatives:

\[dY_t = d(\log X_t) = 0 + \frac{1}{X_t} dX_t + \frac{1}{2} \left(-\frac{1}{X_t^2}\right) (\sigma X_t)^2 \, dt\] \[= \frac{1}{X_t} dX_t - \frac{1}{2} \frac{\sigma^2 X_t^2}{X_t^2} \, dt = \frac{1}{X_t} dX_t - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} dt\]Step 3: Substitute the original SDE. From equation (7), we have $dX_t = \mu X_t \, dt + \sigma X_t \, dW_t$. Substituting:

\[dY_t = d(\log X_t) = \frac{1}{X_t} (\mu X_t \, dt + \sigma X_t \, dW_t) - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} dt\] \[= \mu \, dt + \sigma \, dW_t - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} dt = \left( \mu - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} \right) dt + \sigma \, dW_t.\]Notice how $dY_t$ no longer depends on the state—we’ve turned it into something simple.

The Itô correction. See that $-\frac{\sigma^2}{2}$ term? That’s entirely from the second-order derivative in Itô’s Lemma. Without it, we’d get the wrong answer. This is a fundamental difference from ODEs: the nonlinearity of the logarithm interacts with the noise to create an extra drift term that wouldn’t exist in deterministic calculus.

Now you should see that the r.h.s of the SDE looks “nicer” and can be solved with the ingredients mentioned in the Stochastic Integrals section via integration.

Step 4: Integrate both sides (write the solution as integral form). Now we integrate both sides from $0$ to $t$:

\[\int_0^t dY_s = \int_0^t \left( \mu - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} \right) ds + \sigma \int_0^t dW_s.\]The left side gives $Y_t - Y_0$ by the fundamental theorem of calculus.

The first integral on the right is ordinary: $\int_0^t \left( \mu - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} \right) ds = \left( \mu - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} \right) t$.

The second is a stochastic integral: $\sigma \int_0^t dW_s = \sigma (W_t - W_0) = \sigma W_t$ (since $W_0 = 0$).

Therefore

\[Y_t - Y_0 = \left( \mu - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} \right) t + \sigma W_t.\]Step 5: Solve for $Y_t$. Rearranging terms gives

\[Y_t = Y_0 + \left( \mu - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} \right) t + \sigma W_t.\]Since $Y_t=\log(X_t)$, we can resubstitute as

\[\log X_t = \log X_0 + \left( \mu - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} \right) t + \sigma W_t,\]and exponentiating both sides gives us the solution to the SDE in equation (7)

\[X_t = X_0 \exp\left( \left( \mu - \frac{\sigma^2}{2} \right) t + \sigma W_t \right). \tag{8}\]Solving the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Process

Let’s return to the OU process (equation 4) and derive its explicit solution. Recall the OU SDE

\[dX_t = -\theta X_t \, dt + \sigma \, dW_t.\]This is a linear SDE, and we can solve it using the integrating factor trick from ODEs. The key idea is to find (again) a transformation that eliminates the drift term such that the transformed SDE only consists of additive noise, i.e. a state independent diffusion term scaled by Brownian motion $dW_t$. (So something “nice” we can solve with knowledge about stochastic integrals.)

Step 1: Choose the transformation. Consider $Y_t = X_t e^{\theta t}$, so $f(X, t) = X e^{\theta t}$. We’ll apply Itô’s Lemma to find $dY_t$.

Step 2: Compute the partial derivatives. For $f(X, t) = X e^{\theta t}$:

- $\frac{\partial f}{\partial t} = X \theta e^{\theta t} = \theta X e^{\theta t}$ (notice here $f$ has time dependency compared to the geometric Brownian motion earlier)

- $\frac{\partial f}{\partial X} = e^{\theta t}$

- $\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial X^2} = 0$ (since $f$ is linear in $X$)

Step 3: Apply Itô’s Lemma. Using equation (5) with $\mu(X_t, t) = -\theta X_t$ and $\sigma(X_t, t) = \sigma$ to derive $dY_t$.

\[dY_t = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial f}{\partial X} dX_t + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial X^2} \sigma^2 \, dt\]Substituting the derivatives:

\[dY_t = \theta X_t e^{\theta t} dt + e^{\theta t} dX_t + \frac{1}{2} \cdot 0 \cdot \sigma^2 \, dt\] \[= \theta X_t e^{\theta t} dt + e^{\theta t} dX_t.\]Step 4: Substitute the original SDE. From the OU process, $dX_t = -\theta X_t \, dt + \sigma \, dW_t$. Substituting:

\[dY_t = \theta X_t e^{\theta t} dt + e^{\theta t} (-\theta X_t \, dt + \sigma \, dW_t)\] \[= \theta X_t e^{\theta t} dt - \theta X_t e^{\theta t} dt + \sigma e^{\theta t} dW_t.\]The drift terms cancel, so this gives

\[dY_t = \sigma e^{\theta t} dW_t.\]Just like before, we’ve transformed it into a state-independent SDE. Let’s solve $dY_t$.

Step 5: Integrate both sides (write the solution as integral form). Integrating from $0$ to $t$:

\[\int_0^t dY_s = \sigma \int_0^t e^{\theta s} dW_s\] \[Y_t - Y_0 = \sigma \int_0^t e^{\theta s} dW_s\]Step 6: Substitute back and solve for $X_t$. Since $Y_t = X_t e^{\theta t}$ and $Y_0 = X_0 e^{\theta \cdot 0} = X_0$:

\[X_t e^{\theta t} - X_0 = \sigma \int_0^t e^{\theta s} dW_s\] \[X_t e^{\theta t} = X_0 + \sigma \int_0^t e^{\theta s} dW_s\]Multiplying both sides by $e^{-\theta t}$:

\[X_t = X_0 e^{-\theta t} + \sigma e^{-\theta t} \int_0^t e^{\theta s} dW_s\]Using the property $e^{-\theta t} e^{\theta s} = e^{-\theta(t-s)}$, we write the final solution to the OU-process as

\[X_t = X_0 e^{-\theta t} + \sigma \int_0^t e^{-\theta(t-s)} dW_s \tag{9}\]The first term is deterministic decay from the initial condition $X_0$. The second term is a stochastic integral where noise at each time $s$ is weighted by $e^{-\theta(t-s)}$, where recent noise contributes more than older noise.

Evaluating the stochastic integral: While we can’t simplify $\int_0^t e^{-\theta(t-s)} dW_s$ further in closed form (it remains a random variable), we can compute its statistical properties using the Itô isometry (equation 2).

Mean (expectation): Taking the expectation of equation (9):

\[\mathbb{E}[X_t] = \mathbb{E}\left[X_0 e^{-\theta t}\right] + \sigma \mathbb{E}\left[\int_0^t e^{-\theta(t-s)} dW_s\right] = X_0 e^{-\theta t} + 0 = X_0 e^{-\theta t}\]The stochastic integral has zero mean (as we showed earlier), so the expected value decays exponentially to zero.

Variance: The stochastic integral is Gaussian with mean zero. Using Itô isometry (equation 2) with $g(s) = e^{-\theta(t-s)}$, we compute the variance:

\[\text{Var}\left[\int_0^t e^{-\theta(t-s)} dW_s\right] = \int_0^t \left(e^{-\theta(t-s)}\right)^2 ds = \int_0^t e^{-2\theta(t-s)} ds\]Rewriting $e^{-2\theta(t-s)} = e^{-2\theta t} e^{2\theta s}$ and pulling out the constant to compute the ordinary integral:

\[= e^{-2\theta t} \int_0^t e^{2\theta s} ds = e^{-2\theta t} \left[\frac{1}{2\theta} e^{2\theta s}\right]_0^t = e^{-2\theta t} \cdot \frac{1}{2\theta}(e^{2\theta t} - 1) = \frac{1}{2\theta}(1 - e^{-2\theta t})\]So the total variance is:

\[\text{Var}[X_t] = \text{Var}\left[\sigma \int_0^t e^{-\theta(t-s)} dW_s\right] = \sigma^2 \cdot \frac{1}{2\theta}(1 - e^{-2\theta t})\]Stationary distribution: As $t \to \infty$, the mean decays to zero ($\mathbb{E}[X_t] \to 0$) and the variance approaches $\sigma^2/2\theta$. Thus $X_\infty \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2/2\theta)$. See Gardiner’s Handbook of Stochastic Methods (Section 4.4) for more details.

The Multidimensional Case

Everything we’ve done extends naturally to vector-valued processes. Consider $\mathbf{X}_t \in \mathbb{R}^n$ evolving as

\[d\mathbf{X}_t = \boldsymbol{\mu}(\mathbf{X}_t, t) \, dt + \boldsymbol{\Sigma}(\mathbf{X}_t, t) \, d\mathbf{W}_t,\]where $\boldsymbol{\mu}: \mathbb{R}^n \times \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}^n$ is the drift vector, $\boldsymbol{\Sigma}: \mathbb{R}^n \times \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}^{n \times m}$ is the diffusion matrix, and $\mathbf{W}_t \in \mathbb{R}^m$ is an $m$-dimensional Brownian motion (with independent components).

For a scalar function $f(\mathbf{x}, t): \mathbb{R}^n \times \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$, Itô’s Lemma generalizes to:

\[df = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} dt + \nabla f \cdot d\mathbf{X}_t + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i,j=1}^n \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_i \partial x_j} (\boldsymbol{\Sigma} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}^\top)_{ij} \, dt \tag{10}\]Breaking down each term:

-

$\frac{\partial f}{\partial t} dt$ — explicit time dependence (same as 1D)

-

\(\nabla f \cdot d\mathbf{X}_t = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i} dX_i\) — first-order change using the gradient $\nabla f = \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}, \ldots, \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n}\right)$

-

$\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i,j} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_i \partial x_j} (\boldsymbol{\Sigma} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}^\top)_{ij} \, dt$ — Itô correction using the Hessian matrix of second derivatives

The key difference from 1D: the Itô correction now involves $\boldsymbol{\Sigma} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}^\top$—the covariance matrix of the noise. This comes from $(dX_i)(dX_j) = (\boldsymbol{\Sigma} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}^\top)_{ij} \, dt$, the multidimensional version of $(dW_t)^2 = dt$.

For the interested reader, I highly recommend looking into Särkkä’s Applied Stochastic Differential Equations4 Theorem 4.2, where a more practical derivation of Itô’s Lemma is shown.

A 2-Dimensional Problem: Brownian Motion on a Circle

Let’s put everything together with a geometric example: Brownian motion on a circle. This is where things get really interesting—we’ll see how Itô’s Lemma handles curved spaces and why the correction term matters geometrically.

Setup

Consider a point moving on the unit circle in $\mathbb{R}^2$. We can parameterize the position as

\[\mathbf{x}_t = (x_t, y_t)^T = (\cos \theta_t, \sin \theta_t)^T,\]where $\theta_t$ is the angle at time $t$. Although the state space is 2-dimensional, the system is effectively 1-dimensional since it’s completely determined by the angle $\theta$.

We let the angle evolve through changes induced by Brownian motion via

\[d\theta_t = dW_t.\]This means the point performs a random walk along the circle, moving clockwise or counterclockwise based on the Brownian increments as shown in the Figure below.

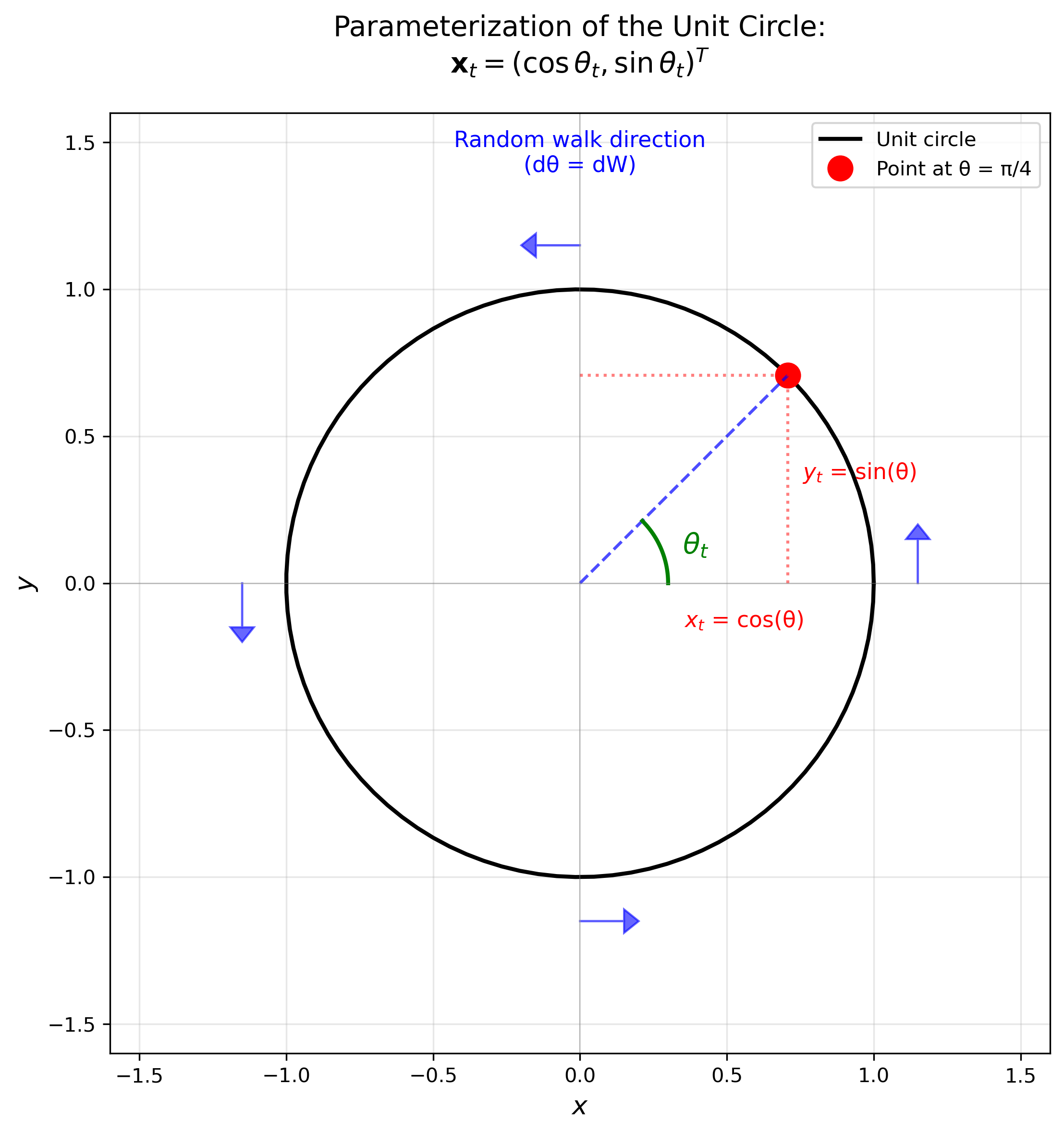

Figure: Parameterization of the unit circle using the angle $\theta_t$. The position $\mathbf{x}_t = (\cos\theta_t, \sin\theta_t)$ is completely determined by the angle, which evolves randomly via $d\theta_t = dW_t$. Blue arrows indicate the direction of the random walk.

Applying Itô’s Lemma

Now for the interesting part: what are the SDEs for the Cartesian coordinates $x_t = \cos \theta_t$ and $y_t = \sin \theta_t$? We’ll apply Itô’s Lemma to each component. The random fluctuations are in $\theta$, but Itô’s Lemma will tell us how they propagate to $(x, y)$.

Step 1: Compute the partial derivatives for $x_t = \cos \theta_t$. For $f(\theta, t) = \cos \theta$:

- $\frac{\partial f}{\partial t} = 0$ (no explicit time dependence)

- $\frac{\partial f}{\partial \theta} = -\sin \theta$

- $\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial \theta^2} = -\cos \theta$

Step 2: Apply Itô’s Lemma to find $dx_t$. Using equation (5) with $\mu(\theta_t, t) = 0$ and $\sigma(\theta_t, t) = 1$ (since $d\theta_t = dW_t$):

\[dx_t = \frac{\partial f}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial f}{\partial \theta} d\theta_t + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial \theta^2} \sigma^2 \, dt\]Substituting the derivatives:

\[dx_t = 0 + (-\sin \theta_t) dW_t + \frac{1}{2}(-\cos \theta_t) \cdot 1^2 \, dt = -\frac{1}{2}\cos \theta_t \, dt - \sin \theta_t \, dW_t.\]Step 3: Compute the partial derivatives for $y_t = \sin \theta_t$. For $g(\theta, t) = \sin \theta$:

- $\frac{\partial g}{\partial t} = 0$ (no explicit time dependence)

- $\frac{\partial g}{\partial \theta} = \cos \theta$

- $\frac{\partial^2 g}{\partial \theta^2} = -\sin \theta$

Step 4: Apply Itô’s Lemma to find $dy_t$. Similarly, using equation (5):

\[dy_t = \frac{\partial g}{\partial t} dt + \frac{\partial g}{\partial \theta} d\theta_t + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2 g}{\partial \theta^2} \sigma^2 \, dt\]Substituting the derivatives:

\[dy_t = 0 + \cos \theta_t \, dW_t + \frac{1}{2}(-\sin \theta_t) \cdot 1^2 \, dt = -\frac{1}{2}\sin \theta_t \, dt + \cos \theta_t \, dW_t.\]Substituting $x_t = \cos \theta_t$ and $y_t = \sin \theta_t$, we get the vector SDE

\[\begin{pmatrix} dx_t \\ dy_t \end{pmatrix} = -\frac{1}{2} \begin{pmatrix} x_t \\ y_t \end{pmatrix} dt + \begin{pmatrix} -y_t \\ x_t \end{pmatrix} dW_t.\]Geometric Interpretation

Look at what’s happening geometrically:

The diffusion term $(-y_t, x_t)^T dW_t$ is orthogonal to the position vector $(x_t, y_t)^T$—this is the tangent direction to the circle, moving the point along the circle’s boundary.

The drift term $-\frac{1}{2}(x_t, y_t)^T dt$ points toward the origin—it compensates for the stochastic motion trying to push the point off the circle due to the second-order Itô correction.

Together, these terms aim to keep the point on the unit circle while it performs Brownian motion in the angular direction. The drift continuously projects the position back onto the manifold, counteracting the curvature effects from the nonlinear transformation $\theta \to (x, y)$.

Simulation: Exact vs. Numerical Methods

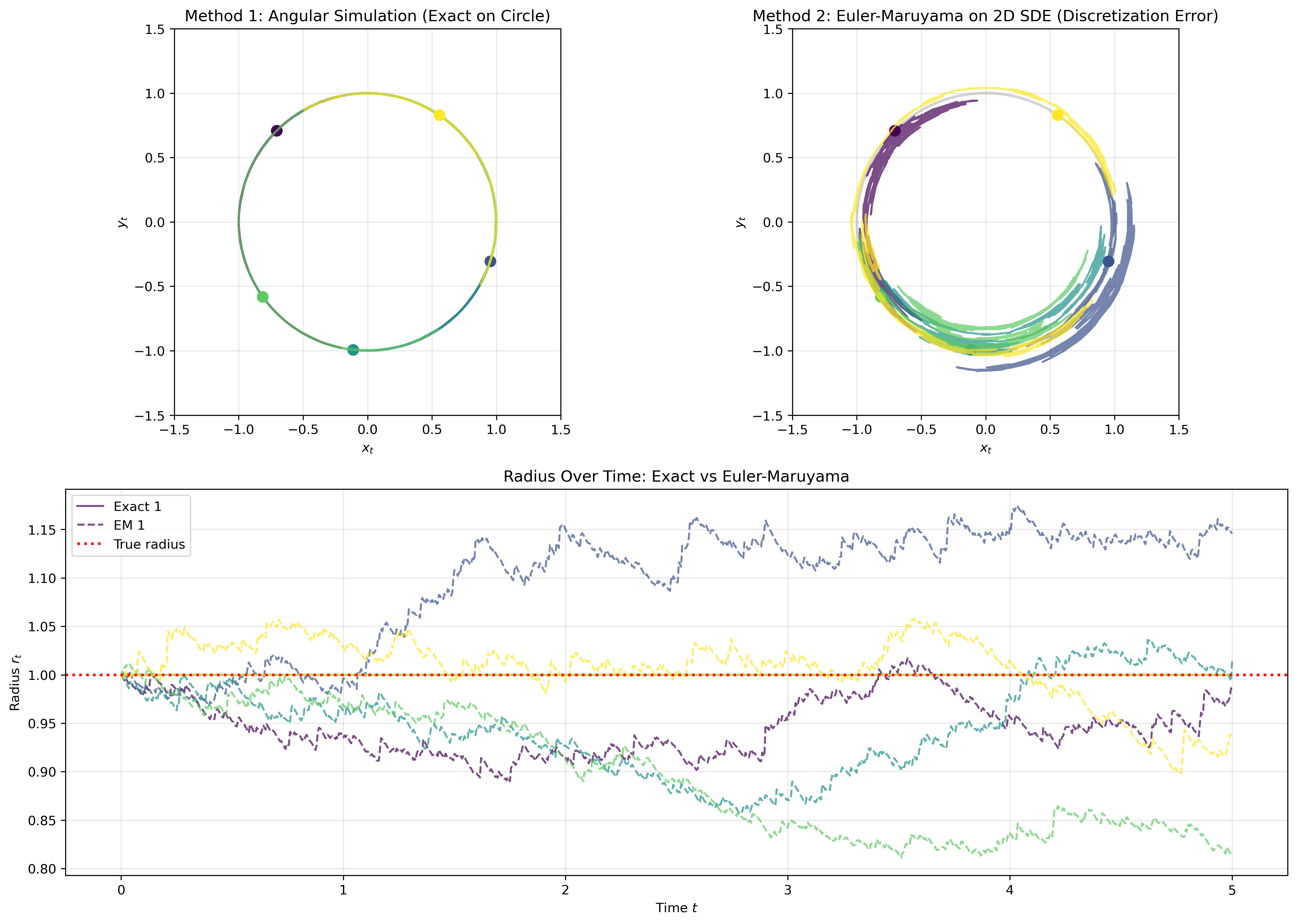

Let’s verify this with simulations comparing two approaches.

Method 1: Angular simulation (exact). We directly simulate $d\theta_t = dW_t$ and convert to Cartesian coordinates $(x_t, y_t) = (\cos \theta_t, \sin \theta_t)$. This stays exactly on the circle by construction.

Method 2: Euler-Maruyama on the 2D SDE (numerical approximation). We discretize the Cartesian SDE using the Euler-Maruyama scheme

\[\begin{pmatrix} x_{t+\Delta t} \\ y_{t+\Delta t} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} x_t \\ y_t \end{pmatrix} - \frac{1}{2} \begin{pmatrix} x_t \\ y_t \end{pmatrix} \Delta t + \begin{pmatrix} -y_t \\ x_t \end{pmatrix} \Delta W_t.\]This numerical scheme has discretization error—it doesn’t keep the point exactly on the circle. The drift only approximates the continuous projection onto the manifold.

Show simulation code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

np.random.seed(42)

T = 5.0

n_steps = 1000

n_paths = 5

dt = T / n_steps

t = np.linspace(0, T, n_steps + 1)

# Method 1: Simulate angular BM (stays exactly on circle)

theta_exact = np.zeros((n_paths, n_steps + 1))

theta_exact[:, 0] = np.random.uniform(0, 2*np.pi, n_paths)

for i in range(n_steps):

dW = np.sqrt(dt) * np.random.randn(n_paths)

theta_exact[:, i+1] = theta_exact[:, i] + dW

x_exact = np.cos(theta_exact)

y_exact = np.sin(theta_exact)

# Method 2: Euler-Maruyama on the 2D SDE (has discretization error)

np.random.seed(42) # Same random numbers for fair comparison

x_em = np.zeros((n_paths, n_steps + 1))

y_em = np.zeros((n_paths, n_steps + 1))

x_em[:, 0] = np.cos(theta_exact[:, 0])

y_em[:, 0] = np.sin(theta_exact[:, 0])

for i in range(n_steps):

dW = np.sqrt(dt) * np.random.randn(n_paths)

# Euler-Maruyama step

x_em[:, i+1] = x_em[:, i] - 0.5 * x_em[:, i] * dt - y_em[:, i] * dW

y_em[:, i+1] = y_em[:, i] - 0.5 * y_em[:, i] * dt + x_em[:, i] * dW

# Compute radii

radii_exact = np.sqrt(x_exact**2 + y_exact**2)

radii_em = np.sqrt(x_em**2 + y_em**2)

# Create visualization

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14, 10))

gs = fig.add_gridspec(2, 2, height_ratios=[1, 1])

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(gs[0, 0])

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(gs[0, 1])

ax3 = fig.add_subplot(gs[1, :])

colors = plt.cm.viridis(np.linspace(0, 1, n_paths))

# Plot 1: Exact method

circle1 = plt.Circle((0, 0), 1, color='lightgray', fill=False, linewidth=2)

ax1.add_patch(circle1)

for i in range(n_paths):

ax1.plot(x_exact[i], y_exact[i], alpha=0.7, linewidth=1.5, color=colors[i])

ax1.plot(x_exact[i, 0], y_exact[i, 0], 'o', markersize=8, color=colors[i])

ax1.set_xlim(-1.5, 1.5); ax1.set_ylim(-1.5, 1.5)

ax1.set_aspect('equal'); ax1.grid(alpha=0.3)

ax1.set_xlabel('$x_t$'); ax1.set_ylabel('$y_t$')

ax1.set_title('Method 1: Angular Simulation (Exact on Circle)')

# Plot 2: Euler-Maruyama

circle2 = plt.Circle((0, 0), 1, color='lightgray', fill=False, linewidth=2)

ax2.add_patch(circle2)

for i in range(n_paths):

ax2.plot(x_em[i], y_em[i], alpha=0.7, linewidth=1.5, color=colors[i])

ax2.plot(x_em[i, 0], y_em[i, 0], 'o', markersize=8, color=colors[i])

ax2.set_xlim(-1.5, 1.5); ax2.set_ylim(-1.5, 1.5)

ax2.set_aspect('equal'); ax2.grid(alpha=0.3)

ax2.set_xlabel('$x_t$'); ax2.set_ylabel('$y_t$')

ax2.set_title('Method 2: Euler-Maruyama on 2D SDE (Discretization Error)')

# Plot 3: Radius over time

for i in range(n_paths):

ax3.plot(t, radii_exact[i], alpha=0.7, linewidth=1.5,

color=colors[i], linestyle='-')

ax3.plot(t, radii_em[i], alpha=0.7, linewidth=1.5,

color=colors[i], linestyle='--')

ax3.axhline(1, color='red', linestyle=':', linewidth=2, label='True radius')

ax3.set_xlabel('Time $t$'); ax3.set_ylabel('Radius $r_t$')

ax3.set_title('Radius Over Time: Exact (solid) vs Euler-Maruyama (dashed)')

ax3.legend(); ax3.grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig("/Users/tuanle/Desktop/projects/tuanle618.github.io/assets/img/blogs/stochastic-calculus/brownian_circle.png",

dpi=300, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

Figure 4: Comparison of exact (angular) vs. approximate (Euler-Maruyama) methods for Brownian motion on a circle. Top: trajectories on the circle. Bottom: radius evolution showing discretization errors.

Figure 4: Comparison of exact (angular) vs. approximate (Euler-Maruyama) methods for Brownian motion on a circle. Top: trajectories on the circle. Bottom: radius evolution showing discretization errors.

The exact angular method (left) stays perfectly on the circle, while Euler-Maruyama (right) drifts off slightly. You can see this in the bottom panel where the dashed lines deviate from radius 1.0. Working directly with the intrinsic coordinate $\theta$ gives exact results, but the Cartesian discretization has errors that accumulate over time.

A Lie algebraic perspective: Notice that the diffusion term $(-y_t, x_t)^T dW_t$ can be rewritten using a Lie algebra matrix. Define

\[A_\theta = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}.\]Then the infinitesimal rotation can be expressed as

\[\begin{pmatrix} -y_t \\ x_t \end{pmatrix} dW_t = A_\theta \begin{pmatrix} x_t \\ y_t \end{pmatrix} dW_t.\]The matrix $A_\theta$ is an element of $\mathfrak{so}(2)$, the Lie algebra of the rotation group $SO(2)$. This is the generator of infinitesimal rotations. This perspective generalizes nicely to Brownian motion on higher-dimensional manifolds, where the diffusion term is written as a Lie algebra element acting on the current position. This is an interesting connection of stochastic dynamics on Lie groups and their applications in diffusion models on manifolds. We will dive deeper into this in the next blogpost.

Conclusion

That’s the essence of stochastic calculus. Starting from the surprising fact that $(dW_t)^2 = dt$, we built up stochastic integrals, discovered Itô’s Lemma, and used it to solve classic SDEs like geometric Brownian motion and the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process. The key technique? Finding clever transformations that turn complicated state-dependent equations into simple ones we can integrate. The final example—Brownian motion on a circle—showed how geometry, randomness, and Itô’s correction all come together, pointing toward deeper connections with Lie groups and manifolds.

References

-

Yang Song, Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, Diederik P Kingma, Abhishek Kumar, Stefano Ermon, & Ben Poole (2021). Score-Based Generative Modeling through Stochastic Differential Equations. In International Conference on Learning Representations. ↩ ↩2

-

Øksendal, B. (2003). Stochastic Differential Equations. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ↩ ↩2

-

Gardiner, C. (2010). Stochastic Methods: A Handbook for the Natural and Social Sciences. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ↩ ↩2

-

Särkka, S., & Solin, A. (2019). Applied Stochastic Differential Equations. Cambridge University Press. ↩ ↩2 ↩3